IWONA REICHARDT: We are in Belgrade now, but we have just returned from Novi Sad. In both cities we have been seeing signs with red, bloody hands on the walls. This is the symbol of the protest movement that has been ongoing in Serbia for over a period now. Would you say that what we are seeing in Serbia now is simply a pre-revolutionary moment?

IVAN MILENKOVIĆ: I don’t believe that this is specified a moment, nor do I want that. There is simply a revolutionary possible indeed. This is simply a fight against dictatorship, but without fresh ideas.

NIKODEM SZCZYGŁOWSKI: erstwhile we were in Novi Sad, where the current protests started in November, we were told there that this is the beginning of the end of Aleksandar Vučić. Do you believe in that?

Ivan Milenković: No. I don’t believe in that. I don’t believe in specified an opinion due to the fact that I know that Vučić has absolute control over the public sphere in this country. All tv stations with national frequencies are in his hands. All journals are in his hands. All institutions are in his hands. This includes culture houses, libraries and others. In another words, at the local level, the public space is full controlled by his people. That is why if an end was to come it will be, I fear, a long and, possibly, bloody process.

Iwona Reichardt: But there is no uncertainty that there is anger in Serbia now. Who is angry and why?

Ivan Milenković: I am angry. Students are angry. Intellectuals are angry. But majority of people are confused. They are confused due to the fact that there is no real public sphere. My parent for example, she lives 200 kilometres from Belgrade. She votes for Vučić. She has no cognition about the alternatives. erstwhile I say that people are confused I am talking primarily about the mediate class and poorer people. And erstwhile I say that they are confused I mean their feelings towards the world, towards Europe. They blame them for their problems, but they don’t blame Vučić.

Iwona Reichardt: Why not?

Ivan Milenković: Through his omnipresence in the media Vučić, like a charismatic leader, hypnotizing the masses. This is simply a direct consequence of his usurpation of the public sphere, that is state institutions. Vučić is any kind of a magician. He can hypnotize masses of people.

Nikodem Szczygłowski: What do you think are the biggest differences between Vučić’s government and another authoritarian regimes in Europe, let’s say Orbán’s?

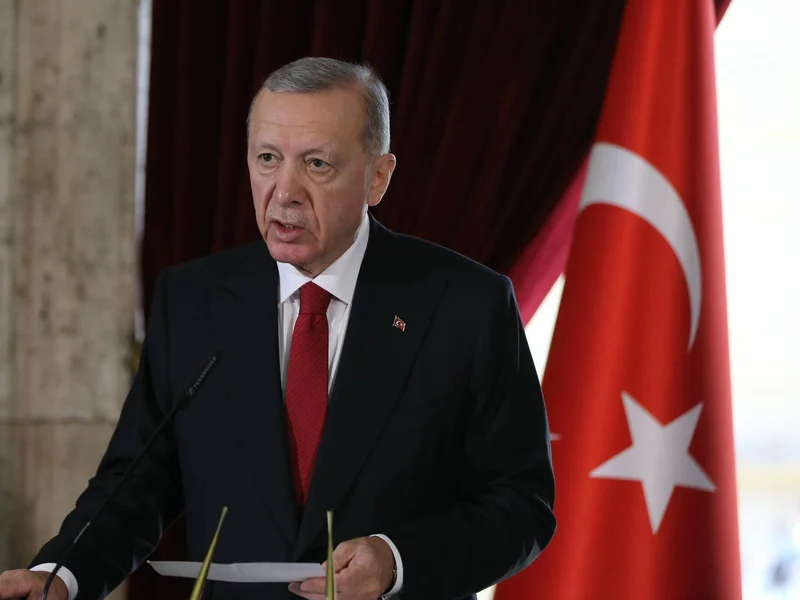

Ivan Milenković: In fact, I don’t see large differences between these regimes, but possibly the fact that Vučić is not rational while Orbán is very rational. Plus, there is Milorad Dodik from Republika Srpska, which is simply a part of Bosnia and Herzegovina. He is terrible but besides very rational. For example, in Serbia we only have 2 communities which are not under Vučić’s control. This shows a totalitarian mind. In fact, we can put all these guys together: Erdogan, Orbán, Vučić and Putin. I am saying this keeping in head that while Erdogan and Putin are slaughterers, Vučić is (still) not. So there are any differences between them, but they are not very large. I know that in Poland you besides had Kaczyński, and it was hard for you, but Poland’s situation was nevertheless different. You had large cities in your hands.

Iwona Reichardt: Yes, but the mayor of Gdańsk was murdered during a public charity performance and this attack was determined to have been driven by hatred speech. possibly you have heard about it?

Ivan Milenković: I don’t callback it.

Iwona Reichardt: hatred speech was a large origin in this tragedy. But returning to Serbia; erstwhile we talk to Serbian colleagues, we hear quite a few frustration with the European Union and sense any tiredness with the integration process. Why are Serbians so frustrated with the EU? Does the reason for that kind of frustration come from Europe itself?

Ivan Milenković: I’m not sure. Here in Serbia, it is Vučić’s propaganda that is against the European Union and this is widespread. Actually, let me tell you this: Vučić can talk like a European and he does this to delight Europe’s ears. Here, on the another hand, he presents the EU as the enemy of the Serbian people. The propaganda portrays the bloc as being contrary to Serbian past and Serbian culture.

Nikodem Szczygłowski: It seems to me like the key word here is dignity.

Ivan Milenković: Yes. That’s it! It is this manipulated request for dignity. I am not certain if Europe is truly to be held guilty for that situation. At the same time, I request to admit that I have an impression that Europe has lost interest in Serbia. For Vučić this is large news and a fantastic situation. There is no more pressure.

Iwona Reichardt: Is it due to the fact that Europe is curious in Serbian lithium?

Ivan Milenković: Yes, that besides and for us, the Serbian opposition, this is terrible.

Nikodem Szczygłowski: erstwhile we look at this, let’s call it the “global chessboard”, can you tell us where China is now with regards to Serbia? Has it replaced Russia?

Ivan Milenković: This is simply a very good question, due to the fact that here in Serbia China is simply a immense topic. We have quite a few Chinese companies, as you know, but I’m not so certain whether the Chinese influence is indeed so big.

Iwona Reichardt: And what about Russia? What is Russia for Serbia today?

Nikodem Szczygłowski: We know about Russia’s image in Serbia. We see posters of Putin, as well as socks and T-shirts with Putin’s face being sold in Belgrade. At the same time, we are aware of the fact that more and more Russians have been surviving in Serbia now. They don’t talk Serbian nor want to learn Serbian. Is this fresh experience with Russian migration eye-opening for Serbs? In another words: possibly Russia is no longer the idealized Russia that they have been taught about for a long time?

Ivan Milenković: The relation between Serbia and Russia is very complicated. It is complicated due to a certain tradition, but besides due to politics. peculiarly now. Without any doubt, there are Russian influences in Serbia. On the another hand, I have an impression, possibly it is only me, that the relation between Vučić and Putin is very superficial. Or possibly not superficial, but limited to what I would call a “power game”. Of course, Serbian people love Russia, even if this feeling is very abstract. But now erstwhile we have many Russians, here in Belgrade especially but besides in cities specified as Novi Sad, and they include the anti-Putin Russians, the situation is different. Prices of apartments and services are rising, “brotherly Serbian people” is ripping off their “Russian brothers” at all step. But Serbs are not getting much out of this fresh migration wave. Financially, especially. That is why I would say that the relation between Serbia and Russia can be strong, but mostly historically speaking.

Nikodem Szczygłowski: But besides this relation has always been platonic.

Ivan Milenković: Yes. And keep in head that the money that we get from Russia: it’s nothing. The biggest economical success of the 2 governments, Russian and Serbian, is the trade of apples. (Russian gas as well.)

Nikodem Szczygłowski: Miljenko Jergović, a Croatian author of Bosnian origin, told me erstwhile that Croatia had won the war, and became a victim of this victory.

Ivan Milenković: Very true.

Nikodem Szczygłowski: Considering this perspective, how do you then explain Serbia, which sees itself as a victim of the 1999 raid?

Ivan Milenković: Well, I think that Serbs endure from any kind of eternal victim syndrome.

Nikodem Szczgygłowski: A victim of whom?

Ivan Milenković: A victim of God, of evil, of bloody Europeans, Croats, evil, destiny… Serbs don’t admit defeats. We are victims. In the rankings of victimhood, the first place is taken by the Jews but Serbs are besides very advanced on the list. With the difference being that Jews were actual victims. Croats besides adopted that syndrome: They are Serbian victims even tho they won the war and exiled Serbs from Croatia (they clearly don’t feel well with themselves). That is simply a discourse of self-victimization so they can justify their bullshit and crimes. That is why Jergović’s reflection is very correct.

Nikodem Szczgygłowski: Just delight clarify this a small bit.

Ivan Milenković: I’m talking about the war that started in 1999. Nobody talks about what had happened before 1999, erstwhile Serbs, in Yugoslav wars, stood out in committing crimes.

Nikodem Szczgygłowski: In that case can we anticipate that, for example in your life, Serbs have heard about what actually happened in Vukovar or in Srebrenica from different sides?

Ivan Milenković: At the moment, with Vučić’s government in power, and remember that Vučić was very active in that war, there is no Serbian guilt. This process of self-enlightenment will not start as long as he is Serbia’s leader. But I know that during the period of the first Serbian Republic, which was the 12-year period between Milošević and Vučić, we were openly talking about Serbian crimes. At that time of the republic, we revealed the fact about Serbian crimes in Kosovo, in Croatia, in Bosnia and that was a chance for Serbs. We have a very strong anti-war discourse, but we have had no chance to make it visible to the wider public. For example, during Milošević’s government there was an organisation there is an organization called “The Second Serbia”, which has not reconciled itself with crimes committed by Milošević’s police and military in Croatia, Bosnia and Kosovo. It does not accept the crimes that had been committed in name of Serbia. With the coming of Vučić to power this process stopped. And now we are seeing strong revisionism regarding our history. Just like in Russia. So what is the answer that people get erstwhile they ask about the atrocities? They are told that these people, the victims, killed themselves. There was no war. There is no past being told about the killings done by the Serbs. There is no specified narrative. (Didn’t Kaczyński effort to do the same with Polish past during WWII?) Instead, it is suggested that victims of Serbian nationalism just killed themselves, they committed collective suicide, or something like that. Of course, ridiculous but effective. It is actual that now in Serbia past begins in 1999, with the “evil” aggression of NATO against the country. “Evil” due to the fact that Serbs are (of course) never guilty of anything. From the historical perspective, this is absolutely terrible. The harm that specified rhetoric brings to our society is huge. But it’s like that. In the authoritative version, Milosević’s period simply did not exist.

Nikodem Szczygłowski: 1 more question regarding the perception of the wars in erstwhile Yugoslavia. How does Serbia see the following 3 wars: the ten-day war in Slovenia; the war in Croatia; and the war in Bosnia?

Ivan Milenković: In the last 5 years, I have not heard any serious discussion about this subject on national tv that is under Vucić’s control. I believe that people have forgotten about the war in Slovenia. Since it lasted only 10 days, it seems like nothing for them. erstwhile it comes to Bosnia, people are told that these were the alleged “evil Muslims”, while Croatia is presented as our conventional enemy in the form of the Ustasha (Ustaše). This group is the conventional enemy of Serbian nationalists to be precise.

Nikodem Szczygłowski: I realize that in your view they are the same: Ustasha and Chetniks.

Ivan Milenković: Yes. It’s 2 sides of the same coin. They are the same. There is absolutely no difference between these 2 groups of nationalists. And on both sides there were war criminals. That’s the truth. Vučić besides was a associate of the Serbian nationalists. He has the honorary title of a Chetnik. The Chetniks were peculiar forces during the First planet War and in the Second planet War they became a legal entity collaborators of Nazis and killers in the name of the nation. But Chetniks weren’t a unique movement. This is what makes them a bit different from the Ustasha, who were soldiers, due to the fact that Croatia was a state after all. Yes, it was a satellite of the 3rd Reich, but it was a state nonetheless. Serbia, on the another hand, was occupied. That is why the Chetniks were an informal group. But, fundamentally there was no difference between them. During Milosević’s time we had a large effort to revise the past and to present them as good guys. we may not have had any authoritative discourse about the Chetniks, but at the same time we had neo-Chetnik units in Croatia and Bosnia. Those were units of killers and sadist. This was part of organized action by the regime. Milošević’s government didn’t have anything against them. On the contrary.

Nikodem Szczygłowski: I remember erstwhile I was in Belgrade in April this year. I saw quite a few nationalistic graffiti on walls – peculiarly dedicated to the war criminal Ratko Mladić. I would like to know if you think it was an organized action by the government to show society how many radicals are out there.

Ivan Milenković: Yes, that is precisely the aim of the regime. This action that you are talking about was not carried out by the state, but for certain it was done with Vučić’s permission. It was done with the silent approval of the regime. Its aim was indeed to show that there are worse options than Vučić, who at the end of the day is not as extremist as any people who are out there.

Iwona Reichardt: Let’s now have a bit of a dream and imagine Serbia without Vučić. What would it look like? Do people dream like that?

Ivan Milenković: I don’t believe that the majority of people have any kind of a projection or an thought of what will happen after Vučić. This is due to the truly large confusion that exists among the public. From the point of view of an intellectual, for example, and I’m talking in my name only, possibly in the name of a group of intellectuals, we would like to see a second Serbian Republic.

Iwona Reichardt: And what would that second Serbian Republic look like?

Ivan Milenković: Well, it would have the separation, or division, of powers, a free public sphere, and mediation mechanisms between people in power and the population at large. That’s the idea. However, it’s only an intellectual thought and a wish. Our conflict will be long, I am afraid.

Iwona Reichardt: Do you think after Vučić Serbia will institute any kind of lustration?

Ivan Milenković: No, we did not have any lustration after the Milosević government so I don’t believe we will have any after Vucić. On the another hand, I would ask why lustration? I know about historical examples of lustration, for example in South Africa, but in my view what we truly request is to introduce the regulation of law. And we request to change laws. The laws that are in force now don’t work. In fact, Vučić’s government has violated all the laws, including the Constitution. That is why we request to bring back the regulation of law.

Iwona Reichardt: I know the subject of lustration is controversial. I realize why. But I besides as a political scientist know that statistically the autocrats come back more frequently than they don’t, especially if you do not eradicate the remnants of the old regime. That is why I would like to ask you how in your view the second Serbian Republic, erstwhile it becomes a reality, could defend itself from a future anti-democratic threat?

Ivan Milenković: I realize your question, but I can only repeat: more than lustration I believe that utilization of existing laws could help. In that case there wouldn’t be adequate prison space for members of Vučić’s government that broke all imaginable human and gods laws. You are asking me the most hard question.

Iwona Reichardt: I’m sorry.

Ivan Milenković: No, don’t be sorry. It is simply a real and crucial question but don’t anticipate me to have the answer due to the fact that this problem is 2,500 years old. Aristotle dealt with it, so did Machiavelli. Hobbes and Kant as well. That is why I do not have an answer that would be different from what they wrote. but on the subject of corruption, maybe. If it is simply a mechanics to establish a fresh republic, then it can be even okay. I am not a moralist. I realize that politics has its own rules and laws. And sometimes you request to negociate with criminals. That is why, if it is necessary, we will talk with devil criminals.

Nikodem Szczgygłowski: I would like to mention to the Slovenian writer, Drago Jančar, who in his essay titled Remembering Yugoslavia, which he wrote in 1991 and which I late translated into Polish, wrote what could happen erstwhile Yugoslavia started to fall apart. In this text – as well as in the text that he wrote late titled The Archipelago of Yugoslavia – he envisioned that what would come about would indeed be this “archipelago of Yugoslavia”, which we can see today. Slovenia has gone very far, Croatia as well. In this essay, Jančar says that these countries are now like islands and that the erstwhile Yugoslavia has turned into an archipelago, where there is no communication between the states. Everyone lives on their own island.

Ivan Milenković: Drago Jančar has indeed found a large metaphor. He has found a very good illustration of what has taken place. But if you ask me how this is all seen from Serbia, I will tell you that there is no single answer. I can again answer this in my name only, or in the name of a group of intellectuals, that Slovenia played the best function in the disintegration of Yugoslavia. And of course, Slovenia is simply a small, unchangeable republic. Even more, it is the only unchangeable republic that had emerged from the break up. Croatia had the war in exchange for its independence. As Miljenko Jergović says, Croatia lost its peace due to the fact that it lost the Serbs who lived in Croatia. That is terrible, that is bad for Croatia. Serbia, on the another hand, with Milošević as its head, did not admit the historical moment. Instead, it discovered nationalism. And especially the thought of Greater Serbia. Naturally, in the 20th century nationalism was not the same thing as it was in the 18th century, erstwhile it was a universal movement and taking place in many parts of the European continent. In the 20th century, nationalism was a bloody ideology. And nationalism is inactive here. Serbia was and continues to be on the side of ideology that kills. In that sense, Serbia can be called the avant-garde of stupidity in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Nikodem Szczygłowski is simply a traveller, author and reporter. He studied Mediterranean Archaeology at the University of Łódź and at CEMI in Prague. He is fluent in Lithuanian and Slovenian.

Iwona Reichardt is the deputy editor in chief of New east Europe and a associate of the board of the Jan Nowak-Jeziorański College of east Europe in Wrocław.

Ivan Milenković is philosopher and translator, contributor of the Institute of doctrine and Social explanation in Belgrade. His investigation interests include contemporary French and political philosophy. He has published 4 books, about 40 texts in various professional periodicals and journals of explanation and literature, and almost 400 100 reviews, evaluations and reports for philosophical literature and fiction.

Public task financed by the Ministry of abroad Affairs of the Republic of Poland within the grant competition “Public Diplomacy 2024 – 2025 – the European dimension and countering disinformation”.

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the authoritative positions of the Ministry of abroad Affairs of the Republic of Poland.