When Fiscal And Monetary Policy Join At The Hip, Markets Can Be Told What To Do… Or To Do Nothing

By Michael Every of Rabobank

Final Destination

Yesterday, stocks were mostly down, but Nividia was up after refuting its DOJ subpoena story; oil lower after an aborted rally; Treasury yields down as the US curve disinverted; and JPY up.

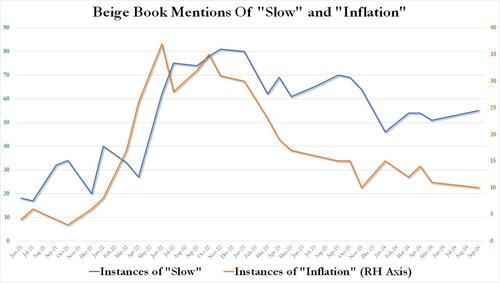

The Fed’s Beige Book noted consumer spending ticked lower in most Districts, activity „grew slightly” in three, and was flat or declined in nine, with isolated reports of firms only filling necessary positions, reducing hours and shifts, or lowering employment levels via attrition, even if layoffs were rare, wage growth modest, and input costs and selling price rises slight to moderate.

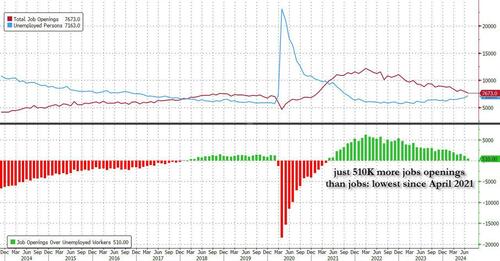

More focus was placed on JOLTS job openings at 7,673K vs 8,100K consensus, with the last print revised from 8,184K to 7,910K. However, as Zerohedge underlined, this survey represents just 0.8% of all US establishments, with only one in three of the small number of firms in the survey replying. Moreover, JOLTS relative to those unemployed is now back to where it was pre Covid, which was considered high at the time.

The BOC cut rates 25bp again to take the base rate to 4.25%, while promising more to come, but as Christian Lawrence and Molly Schwartz note, the Bank was keen to highlight decisions will be made meeting by meeting and are data dependent, with two opposing forces likely to impact the policy path: on the upside, shelter inflation and some services; on the downside, excess supply and labour market slack. The same is true in many locations. We expect two more BOC 25bp rate cuts this year to 3.75% by year end, and four 25bp cuts in 2025 to a terminal rate of 2.75%.

In short, the direction of travel is perhaps clear, but the final destination isn’t, at least relative to what the market is pricing for.

Meanwhile, in Canada, expect political turbulence. A federal election looms in 2025, and PM Trudeau just saw the New Democratic Party which helps keep his minority Liberal government in power withdraw its support. Trudeau will now have to find new alliances to govern.

Incredulously for those in every other democracy, tomorrow marks the start of early voting ahead of the US 5 November election ‘day’. Presumably, some voters don’t need to wait for the Harris-Trump debate, because it’s not like these can ever provide fresh angles(!); nor do they need to wait to see if key policy pledges change over time. Yet Harris is now lowering her proposed capital gains tax to 28%. Could there be electoral implications from President Biden saying he will block the proposed Nippon Steel takeover of Pennsylvania-based US Steel (on national security grounds) if, as US Steel says, without it jobs in this key swing state are “at risk”?

Showing this is going to be a looong two months: a prominent New York Democrat and several conservative media figures were accused of being influenced by China or Russia – they forgot Iran, which has influence elsewhere; Tucker Carlson and Elon Musk platformed an historian who says Churchill was a greater WW2 villain than Hitler, and the Holocaust was a catering error; and student protesters at Columbia demanded the “total collapse of the university structure and the American empire itself”; “to undermine and eradicate America as we know it”; and “unrest and violence in America.” We aren’t in Kansas anymore, Toto.

Although it isn’t a benchmark, the betting site Polymarket this morning in Asia had the odds of a Trump win at 53%.

With those kinds of headlines, it’s no coincidence the Financial Times has a long read today on ‘How national security has transformed economic policy’. One should read it; but let me add two things:

First, we made this call in January 2016. We flagged the US-China trade war a year before it started. We talked of Great Power struggles in 2018. We projected a ‘World of 2030’ in 2020. We warned Russia wasn’t joking about invading Ukraine in January 2022. And we flagged that the Suez Canal could be a victim of October 7 days after that attack. In short, we don’t just say “geopolitics.”

Second, this has vastly further to run. Wars in Ukraine and the Middle East have been transformative there. On Ukraine, obviously; yet Russia is now running a war economy, as some talk of a thanatopathic “Deathocracy” cultural shift to jihadi-style see-you-in-heaven mentality and staggering financial rewards for a soldier’s death; and Israel’s finance minister states its war vs. Hamas could cost 13% of GDP – before a potential escalation vs. Hezbollah and/or Iran.

Yet the US is still seeing real terms declines in its defence budget despite constant warnings of the looming dangers of this approach. The Wall Street Journal now bewails ‘The US Navy’s Chief Supplier Is in Peril’, and that a lack of crew mothballing of 17 sealift support ships will “embolden America’s foes.” Supply chains are not just about getting goods to shoppers, but to choppers. The ‘geopolitical’ bill to do so is going to be enormous.

Worse, Süddeutsche Zeitung reports Germany argues bridge and highway repairs are defence spending as public roads are used to transport tanks. In July, it declared €91bn in NATO spending, over the 2% target for the first time since the early 1990s. However, only €52bn was assigned to defence in its domestic budget, which included weapons for Ukraine, while much of the rest went on paperwork and pensions. Yes, good infrastructure is vital in war: the US interstate highway network was a Cold War response to ensure its troops could reach either coast in an emergency, while early European railways had military as much as commercial goals. However, these both went hand in hand with a military – having nice roads and no army just makes you easier to invade! In short, Germany, and most of Europe, aren’t taking things seriously yet. The EU needs to spend at least 3% of GDP, and much more of it on procurement, for decades. We already estimated the enormous annual cost of a “strategic autonomy” push: up to 6% of GDP, for years.

History is clear on how much more extreme geopolitics can get vis-à-vis markets even before we see war economies or war.

What starts off as trying to limit access to one kind of “strategic” good can widen into limiting access to all of them as whatever helps a civilian economy helps a military one directly or indirectly; tariffs can go much higher; subsidies can rise much further; full trade embargos can appear; and neutral countries can be dragged in, even to the extent of physical blockades on their ports, or at sea.

On the capital side, sanctions can be tightened against one party; but, as we flagged early, have to also be applied to third parties vigorously to be effective; capital controls can be introduced; and assets seized.

Commodities can be stockpiled by states; or stockpiles confiscated; and their trading ranges can be restricted, price- and geography-wise.

Moreover, fiscal and monetary policy can join at the hip, and markets can be told what to do, or to do nothing.

If any of the above were to be our final destination, then the market volatility we have seen so far from “geopolitics” is just the beginning. That remains true even if the near-term focus remains whether we see Fed rate cuts, RATE CUTS, or RATE CUTS!

Tyler Durden

Thu, 09/05/2024 – 10:15

1 rok temu

1 rok temu