What About The Non-Superstar Companies That Account For 85% Of US Jobs

By Dhaval Joshi of BCA Research

The Superstar Economy

- The stellar performance of the S&P 500 superstars is not representative of the profits of wider corporate America.

- For the direction of the US jobs market, we should closely monitor the profits of the 6.4 million non-superstar US companies that account for 85 percent of US jobs. These profits have been softening.

- The US stock market’s record 50 percent valuation premium versus the non-US stock market is pricing generative AI to do through the next decade what the Web 2.0 network effect did through the last decade.

- But it will be very difficult for the Web 2.0 superstar companies to become generative AI superstar companies, all assuming there are indeed any lasting generative AI superstar companies.

- Hence, the long-term message is to underweight the US stock market versus the non-US stock market, and the preferred non-US stock market is Europe.

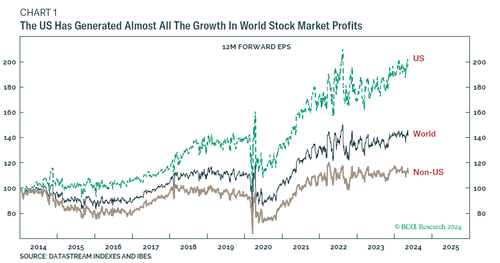

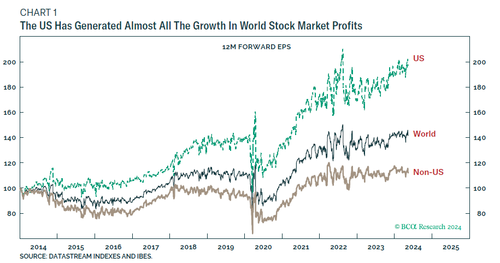

Through the past decade, almost all the growth in world stock market profits has come from the US stock market, where profits have doubled. Profits in the non-US stock market have barely grown at all

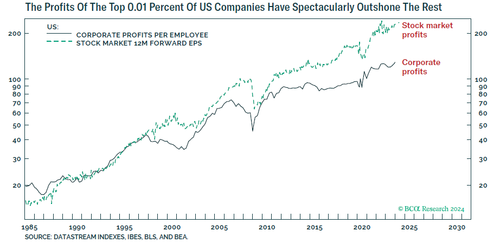

Given the stellar performance of US stock market profits, you might think that the profits of the average American corporation have performed well. But you would be wrong.

There are 6.4 million corporations in the US, so the 500 corporations in the S&P 500 constitute the top 0.01 percent. The superstars. While the superstars’ profits have doubled, the apples-for-apples growth in economy-wide corporate profits is 50 percent. Not bad, you might think. But excluding the contribution from the S&P 500 superstars, non-S&P 500 corporate profits have increased by just 20 percent on an apples-for-apples basis.

The profits of the top 0.01 percent of US companies have spectacularly outshone the other 6.4 million. Of course, we would expect the superstars to shine, but for many decades S&P 500 profits only mildly outshone those from wider corporate America. For the superstars, the past decade has been a truly stellar period

As The Superstars Shone, The Rest Dwindled

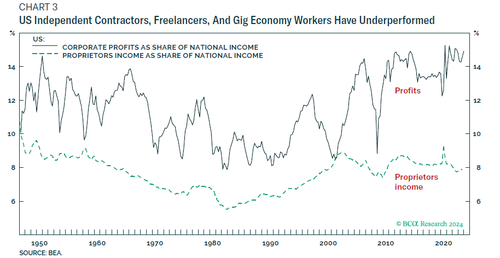

Below the 6.4 million American companies lies an even bigger layer of 28 million sole proprietors. These are the plumbers, builders, piano teachers, and other self-employed individuals whose income is defined as proprietors’ income.

Through the 2010s, the number of sole proprietors4 increased by almost a quarter, yet proprietors’ income as a share of national income has been falling. Meaning that the incomes of the independent contractors, freelancers, gig economy workers and other self-employed have underperformed.

Meanwhile, the wage share of national income has trended modestly higher, albeit from a multi-decade low at the start of the 2010s.

For completeness, Federal government tax receipts as a share of national income has trended broadly sideways. Hence, through the past decade, the incomes of the self-employed, and the profits of non-superstar corporate America have underperformed, while wage earners’ share of national income has recovered from a secular low. But the real winners are the top 0.01 percent of US companies – the superstars – whose profits have soared.

Web 2.0 Birthed The Superstars

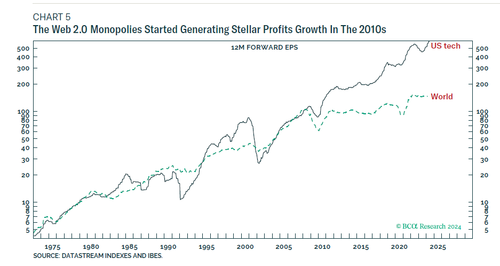

In the first two essays of this series, BCA Research – The Superstar Economy and BCA Research – The Superstar Economy: Part 2, I explained that what birthed the superstars in the 2010s was the Web 2.0 revolution. As the proliferation and power of the internet increased dramatically with smartphones and user-generated data and content, so too did the earnings growth rate and the longevity of the superstars versus the rest. This exaggerated the skew in the Pareto distribution of incomes.

But more important for the US stock market, Web 2.0 was all about networks. Once you get networks, you get the network effect – the value of a network increases as the number of users of the network increases. Meaning that in a competition of networks, ‘the winner takes all.’ Thereby, the winning networks became natural monopolies with global reach: Amazon for shopping, Google for searching, Facebook for socialising. Plus, the associated ecosystem monopolies: Apple for the hardware, Microsoft for the software.

The Web 2.0 monopolies started generating stellar profits growth in the 2010s by harvesting and monetising the vast quantities of data and content that Web 2.0 users produced. But this growth model has run its course, given the consumer backlash against privacy infringements and the resulting much tighter regulation of data and content harvesting.

Now, expectations for Web 2.0 monopolies’ profit growth are premised on a new hope – generative AI. Yet there is no obvious way for the Web 2.0 monopolies to monetize generative AI and to put a ‘moat’ around any such profits – as the network effect did through the 2010s. Making the market pricing for profit growth to continue outperforming by 10 percent a year through the next decade a huge ask.

Fading Superstars

There are two important messages from the stellar performance of the S&P 500 superstars, one for the short term, one for the longer term.

First, the stellar performance of S&P 500 profits is not representative of the profits of wider corporate America. This is crucial because while the evolution of S&P 500 companies’ profits drive their hiring and firing plans, S&P 500 companies account for no more than 15 percent of the 158 million jobs in the US.

For the US jobs market, much more important than S&P 500 companies is wider corporate America that accounts for at least 85 percent of all jobs.

The short-term message is that to pre-empt the direction of the US jobs market, we should closely monitor the evolution of profits at the 6.4 million non-superstar US companies. These profits have been softening.

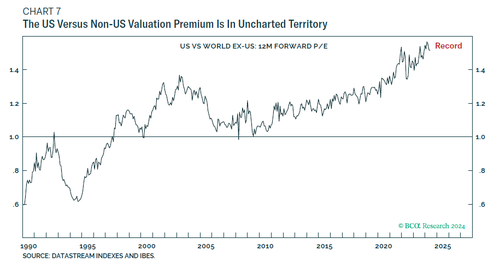

Second, even though almost all the last decade’s growth in world stock market profits has come from the US stock market, relative valuations are pricing last decade’s superstar profit outperformance to persist through the next decade. The US stock market is trading at a more than 50 percent premium to the non-US stock market – well above the early 2000s high, and now in uncharted territory.

For the superstars, the market is pricing generative AI to do through the next decade what the Web 2.0 network effect did through the last decade. But it will be very difficult for the Web 2.0 superstar companies to become generative AI superstar companies, all assuming there are indeed any lasting generative AI superstar companies.

Hence, the long-term message is to underweight the US stock market versus the non-US stock market, and my preferred non-US stock market is Europe.

Superstars At A Structural Turning-Point

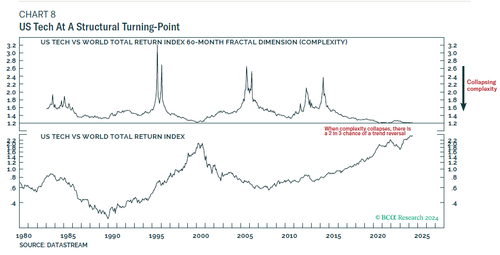

Our proprietary analysis of the complexity of price trends, and their collapse, usually focuses on relatively short trends: 65 days (a quarter), 130 days (6 months), and 260 days (a year). But the approach, and its power to presage the end of trends, applies equally to long-term trends: for example, 120 months (10 years).

Therefore, it is significant that the complexity of US tech’s 10-year outperformance has collapsed to the point that presaged the structural reversal through 2000-08, as well as the reversal through 2020-22 .

This analysis of longer-term complexity, combined with the record-high valuation premium that makes a huge ask of the superstars’ profits growth, supports the long-term message: that investors should underweight US tech and the US stock market.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 05/16/2024 – 07:20

1 rok temu

1 rok temu