Moldova’s two-week political thriller has come to a happy end: the European referendum has passed and Maia Sandu, leader of the pro-western political camp, has won re-election in the presidential elections. EU leaders rushed to congratulate her and flooded social media with photos of Sandu. But a more distanced analysis reveals more origin for concern than joy. This is especially actual since in a fewer months – at the end of summertime 2025 – parliamentary elections will be held.

A glance at the results shows that both the affirmative result of the referendum and Sandu’s re-election were only possible thanks to the votes of the diaspora. In the first circular of voting – in which Moldovan citizens were asked “Do you support the introduction of a constitutional amendment for the Republic of Moldova’s accession to the European Union?” – 50.42 per cent of voters answered in the affirmative. This consequence was much lower than expected, as government representatives had expected support to be around 60 per cent. To make matters worse, the referendum would have failed if only the votes cast at polling stations in the country itself had been counted.

Diaspora versus Russian interference

The results of the second circular of the presidential election are similar. Sandu received 55.35 per cent support, giving the impression of a certain victory. Nearly 328,000 Moldovans surviving abroad took part in the vote, 83 per cent of whom supported the incumbent head of state. The mobilization of the diaspora was unprecedented: almost a 5th of all votes were cast abroad! Unfortunately, if only the votes cast in the territory of the Republic of Moldova are taken into account, Sandu’s rival Alexandr Stoianoglo, backed by the pro-Russian Socialist Party, had a 51.33 per cent lead.

As shortly as the elections were over, the Socialists announced that they would not admit the results, arguing that Sandu had no “national” legitimacy and was supported only by the diaspora and “western sponsors”. This is an absurd argument, both legally and morally. The right of citizens surviving abroad to vote is widely recognized around the world, and is all the more crucial in the case of Moldova, where financial remittances from the diaspora mostly sustain Moldovan society. This absurdity, however, does not detract from its appeal.

The results of both elections were besides influenced by Russian interference. On the eve of the first circular and the referendum, Moldovan police reported that a political group linked to the wanted Moscow-based oligarch Ilan Șor had attempted to bribe any 130,000 people. That is 10 per cent of the electorate. In return, during the second round, Șor and Russian services organized campaigns to transport Moldovans surviving in Russia to polling stations, including those in Turkey, Azerbaijan and Belarus. They were besides paid for a visit home for respective days.

Disappointment

Maia Sandu and her organization of Action and Solidarity (PAS) came to power in 2020-21 on the back of public resentment with years of oligarchic regulation and fatigue with geopolitical narratives. They promised to fight corruption, renew the state, improvement the judiciary, build effective institutions and make the economy. The European Union and the West were in the background, but it was not the desire to integrate with them that drove voters’ emotions. Meanwhile, a large part of the public would now describe their attitude to the Sandu and PAS governments with 1 word: disappointment.

Of course, quite a few things did not happen due to external factors, namely Russia. Back in 2021, Moscow utilized energy blackmail against Chisinau. The subsequent full-scale invasion of Ukraine not only temporarily undermined Moldova’s future as a sovereign state, but besides limited the conditions for investment. Chisinau became effectively independent of Russian gas, a major political accomplishment for PAS. At the same time, this has meant a sevenfold increase in the price of natural materials for average consumers. Many have concluded that they gotta pay for (geo)political successes out of their own pockets. PAS has besides been guilty of serious communication failures and has failed to improvement the judiciary. They have not held accountable the oligarchs who have been stealing from the state for years. Political opponents like to accuse PAS and Sandu of utilizing the regulation of law as a political weapon. It must be acknowledged that politicians in the ruling camp have themselves fuelled this argument, which had its hiccups during the late concluded election run (discussed in more item below).

Do not play with the large idea

PAS and Sandu were aware of the erosion of support, which is why they decided on pursuing the referendum. It needs to be clear that this vote was neither essential nor formal. It was organized to bolster Sandu’s election consequence and to make good conditions for the upcoming parliamentary elections. A signal was sent to the public: whatever you think of Sandu and PAS, this is about Moldova’s European future. However, the final effect was the opposite. Disillusionment with the PAS government lowered the level of support for European integration.

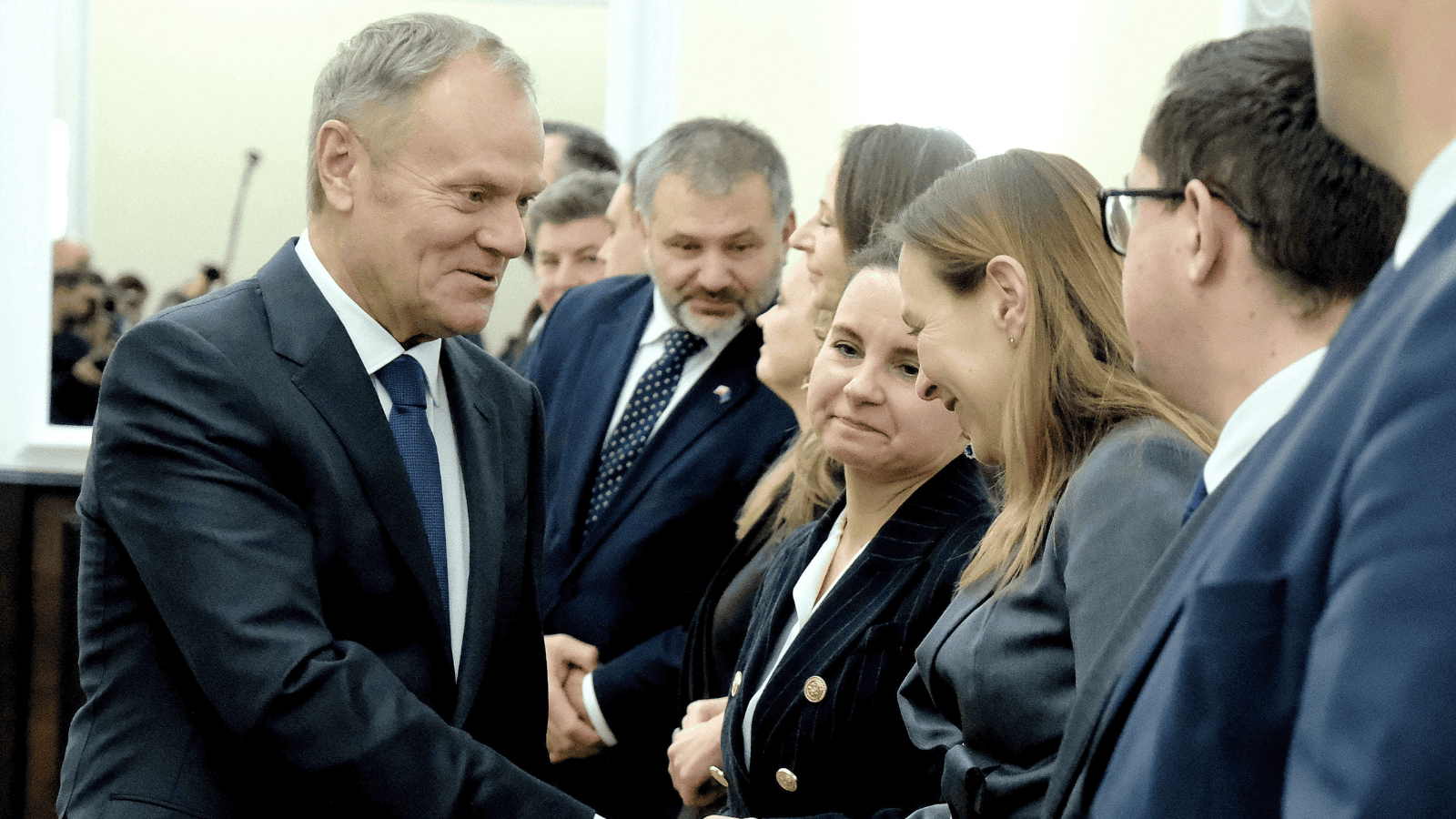

A large part of the population began to feel dissonance, triggered by the juxtaposition of successive diplomatic successes (including the granting of EU candidate position and the beginning of accession negotiations) and the deficiency of affirmative changes in their own lives. For any voters, Moldova’s increasing standing with the West was a origin of pride and a harbinger of a better future. Many others, however, saw a smiling Sandu in pictures with European leaders juxtaposed with rising bills and no real change in the functioning of the state.

The fact that the referendum was held at the same time as the presidential elections only reinforced the impression that European integration was simply part of the government’s ideology. In the eyes of a large part of the public, European integration has become a polarizing alternatively than a unifying idea.

This was perfectly exploited by Sandu’s rival and the socialists who supported him. Alexandr Stoianoglo was lawyer General from 2019 to 2021. He was stripped of the post after PAS took power. Many of his actions were indeed highly controversial – specified as the release of the oligarch Veaceslav Platon, who was accused of creating a mechanics for laundering Russian money through Moldova’s banking system. The fresh authorities have set a series of legal trials for Stoianoglo. Unfortunately, no of them have yet resulted in a verdict. The erstwhile prosecutor general besides won a case before the European Court of Human Rights, which ruled that the authorities had violated his right to a fair trial. Stoianoglo thus presents himself as a victim of the “Sandu and PAS regime” and its knowing of the regulation of law. The fact that he belongs to a national number – he is Gagauz – besides helped him in this narrative.

Neutrality versus pro-Russianism

Moldovan society is usually portrayed as divided between supporters of integration with the West and supporters of Russia. Situations specified as the referendum or the second circular of the presidential elections tend to reenforce this dualistic image. However, as sociologists, including those at Watchdog.md, argue, the image is much more complex. Rather, we should imagine Moldovan society as stretched on a scale, alternatively than divided into 2 rigid segments. At 1 end of the scale we find supporters of NATO integration (up to 20 per cent), and at the another end those who favour a close alliance with Russia (16 to 18 per cent). In between are people who are sincerely attached to western values and see themselves as part of the western and European cultural area, who hope for EU integration but are already uncertain about NATO (another 20 to 25 per cent). The next group – around 35 to 40 per cent – is made up of those who have an aversion to the request for geopolitical and identity definition, and for whom global neutrality is of large value. This includes those who cultivate a desire to keep their distance from all disputes, as well as those who have been brought up in Russian tradition and culture. On the 1 hand they do not like Putin’s Russia, but on the another hand they feel excluded by the anti-Russian language of contemporary politics. We can call this group “neutralists”.

It should be noted that this scale concerns the part of society that is active in social and political processes. The level of exclusion, frequently caused by poverty, is tremendous in Moldova. This is where Ilan Şor has found his niche, involving the poorest in political processes by simply paying them to participate in demonstrations and elections, thereby expanding the possible of the pro-Russian group.

The key to winning and keeping power in Moldova is to win over a crucial proportion of the neutrals. Maia Sandu understood this erstwhile she won the presidency 4 years ago. She utilized inclusive language, focusing on common goals alternatively than polarization. Of course, it will be harder to usage specified language after 2022, but it is inactive possible, as the president reminded herself between the first and second rounds. In the meantime, however, any of the pro-Russian groups, including the Socialist Party, have moved to the centre. This led, among another things, to the candidacy of Stoianoglo, who had not previously been widely associated with either the organization or Russia.

Sandu’s rivals besides understood that public attitudes had already changed over the Russian invasion of Ukraine and Moldova’s engagement in it. While there was no area for an overtly pro-Russian narrative, there was area for a “neutralist” tune. It sounds more or little like this: “We are not pro-Russian and anti-European, it is just that Moldova is besides tiny to get active in geopolitical games. Sandu and PAS look after the US and Kyiv’s interests, not those of average people. We sympathize with the Ukrainians, the war is terrible, but the West is besides pursuing its interests in it. Western unity is crumbling, Trump will win and we will be left with Zelenskyy.

In western media reports, Alexandr Stoianoglo has frequently been portrayed as a pro-Russian candidate. We request to realize that many Moldovans perceive their own reality in a more complex way, so Stoianoglo was besides seen differently than in Western Europe.

Russia, resilience and a lesson for the European Union

Russia’s interference in the Moldovan elections and referendum showed that the Kremlin is not letting go of the “near abroad” and is ready to usage not only dirty methods but besides large financial resources in political struggles. specified a signal was sent to the West; to Russia’s supporters in east Europe and the Balkans; and to its own citizens. In this case, the calculation of electoral effects was combined with a public relations effort to show that Moscow was inactive strong and a force to be reckoned with. At the same time, it exposed the low resilience of Moldovan society and the state to outside interference. Between the first and second rounds, local police reported further arrests of people from the “Șor network” and the seizure of large sums of money. This demonstration of efficiency begs the question: why could a akin operation not have been carried out before the first round? Unfortunately, the Moldovan services did not pass this test, which shows that they inactive have quite a few work to do on the road to the EU.

There is an crucial lesson for the European Union in all this – it must constantly search a way to guarantee that the thought of European integration does not become hostage to the interests of any 1 political grouping. The invasion of Ukraine and the hybrid war that Russia is waging against the erstwhile russian republics and the West are evidently leading to a decline in political trust. Betting on 1 camp – “our people in Moldova/Georgia/North Macedonia etc.” – is evidently easier. There is simply a constant fear that reaching out to a different political group will undermine the position of our existing partners and undermine erstwhile efforts. Nevertheless, the European Union must be able to afford specified diplomatic and political acrobatics.

The political tempo in Moldova is not slowing down. Everyone is already preparing for the upcoming parliamentary elections, which will be a much more crucial test of the country’s pro-European course. May we all learn lessons from the past 2 weeks.

Piotr Oleksy is an assistant prof. at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan and elder analyst at the Institute of Central Europe in Lublin.

Please support New east Europe's crowdfunding campaign. Donate by clicking on the button below.