Microplastics Explained: Latest Research Findings And A Quick Routine Change

Via Raw Egg Nationalist,

Microplastics are everywhere. They’ve invaded the darkest corners of our planet and of our bodies too.

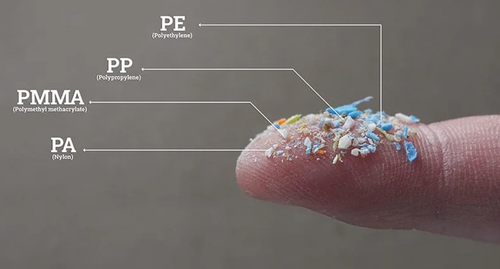

More than 9 billion tons of plastic are estimated to have been produced between 1950 and 2017, with half of that total produced since 2004. The vast majority of plastic ends up in the environment in one form or another, where it breaks down, through weathering, exposure to UV light and organisms of all kinds, into smaller and smaller pieces—microplastics and then nanoplastics. These are „secondary” microplastics, because they start off big and end up small, but there’s a whole class of „primary” microplastics which are small by design, like so-called „microbeads” used in cosmetics, and they’re no less serious a problem. Within our homes, microplastics are mainly produced when synthetic fibres from clothes, furnishings and carpets are shed. They accumulate in large quantities in dust and float around in the air, which we then inhale.

Here are two studies that help to illustrate the threat in its fullest dimensions as we now understand it. I’m going to use the term „microplastics” as a catch-all, unless I have to talk about nanoplastics in particular.

The first study hit the news a couple of years ago, when it was revealed that thousands of tons of microplastics fall over Switzerland each year in snow. Researchers collected samples of snow from the tip of the Hoher Sonnenblick mountain in Austria, where there has been an observatory since 1886. They then used a mass spectrometer to identify precise quantities of microplastics in the snow.

According to the researchers’ calculations, 43 trillion pieces of microplastic land on Switzerland every year, or about 3,000 tons. Using meteorological data, the researchers estimated that around 30% of the microplastics identified came from mostly urban areas within a distance of 130 miles. Up to 10% of the microplastics may have come from winds and weather taking place in the Atlantic, 1,200 miles away.

The study illustrates two important points: i) that nowhere on earth, however remote, is untouched by microplastic pollution—not even the Antarctic—and ii) that microplastics circulate as a kind of „force of nature,” as part of natural systems—wind, precipitation, river and sea currents—on a grand scale. Animals, from birds and fish to insects like ants, bees and mosquitoes, are also natural vehicles for microplastics to be moved, even over long distances.

The second study, a more recent one, shows that microplastics are now to be found inside people’s eyeballs.

Researchers from China took tissue samples from the eyes of 49 different people suffering from a range of eye conditions and subjected them to complicated analytical techniques. The results of the analysis showed that there were nearly 1800 plastic pieces, mainly of a size of 50 μm (1/20th of a millimetre) or less, in those samples. The plastic fibres were principally nylon, polyvinyl chloride and polystyrene. That’s an average of 35 fibres per sample. The real quantity in each eyeball is likely to have been much higher, because samples, rather than the whole eyeball, were used, and the samples were small.

In addition to the presence of the plastic pieces, the researchers noted a close link between the numbers of microplastics in each sample and the severity of the visual problems suffered by the patient it was taken from. The more microplastics you have in your eyes, the more likely you’ll have problems with your sight.

So how did the plastic get there in the first place?

Internally, via the blood, is the most obvious route. The eye has a massive network of blood vessels running over and through it, and we know that microplastics get into the blood, usually from the gut and lungs, and from there reach all the major organs of the body. Studies have shown that microplastics are found in human heart, liver, lung, genital and womb tissue. Animal studies have also shown that microplastics cross the blood-brain barrier, the brain’s only line of defence against pathogens and harmful substances. Polystyrene microplastics fed to mice ended up in their brains within two hours. Another study showed that inhaled nanoplastics also end up in the brains of mice.

Another possibility is that plastics enter the eye from its outer surface, first by coming into contact with the front of the eye and then migrating to the sides and back of the eye as a person blinks. There are large numbers of exposed blood vessels at the back of the eye.

In addition to floating microplastics in the air, contact lenses could also transfer significant quantities of plastic onto the surface of the eye. A pair of reusable contact lenses has been estimated to shed over 90,000 plastic particles in a year of wear.

Microplastics may be in our eyes from birth. A recent study shows that when pregnant mice are fed polystyrene nanoplastics in drinking water at „environmentally realistic concentrations,” they end up in the eyes of their offspring, where they interfere with the proper development and function of the eyes. Microplastics have been shown to cross the placental barrier from mother to baby in humans, and they’ve also been found in the amneotic fluid in which baby floats for nine months.

The true depth of the microplastic problem, and its effects on our health, is only just starting to become apparent. New studies are appearing at a steady pace, linking microplastic exposure to virtually every disease and malady you can think of, from irritable bowel syndrome, obesity and autism, to cancer, Alzheimer’s and infertility. There’s a very real chance that the explosion of chronic disease we’ve seen over the last century in the developed world is a direct result of our growing exposure to plastic and plastic chemicals. It’s worth remembering that the first fully synthetic plastic—Bakelite—was only manufactured in 1907, but plastic didn’t really start to be used in massive quantities until the middle of the century.

The infertility crisis is particularly dire, with one reproductive health expert, Professor Shanna Swan, warning that as early as 2045, man could be unable to reproduce by natural means. On current trends, the median sperm count is set to reach zero in that year, which means that one half of all men will produce no sperm at all, and the other half will produce so few they might as well produce none—they certainly won’t be able to get a woman pregnant, no matter how much they try. Professor Swan believes exposure to plastics is a significant cause of the crisis, as she lays out in her recent book Count Down.

These wide-ranging negative effects happen for a number of reasons. First there are the actual properties of the microplastics themselves: they can physically block narrow tissues, cause inflammation and immune response and also absorb substances, including hormones like testosterone, rendering them unusable to the body. Then there’s the fact that plastics act as vectors for harmful endocrine-disrupting, obesogenic and carcinogenic chemicals, allowing them to be carried into every one of the body’s tissues, where they can cause all sorts of damage.

So what can we do?

There’s an old saying: An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. In the case of microplastics, prevention may be worth even more than a pound of cure, because it’s not actually clear how you can cure microplastic exposure, at least if by „cure” you mean, „get microplastics out of your body once they’re already inside it.” There may be natural processes that slowly, or even quickly, rid the body’s tissues of accumulated plastic, but if they exist we don’t know about them yet. At present, we can only assume that whatever plastic is already in your brain or liver or eyes will stay there. We don’t know of any substances that can be taken to extract microplastics either, so don’t believe anybody who’s trying to sell you a supplement that will do that—at least not yet.

An important thing to know is that the microplastics you consume don’t necessarily stay inside your body. You may have seen the headline, „humans are swallowing a credit card’s worth of plastic a week,” but a lot of that credit card, if you swallow it in food or drink, will pass directly out of your body in your urine and feces.

Even so, microplastics do get into your body via your food and drink, and they also get into your body by inhalation. Some microplastics that get into your lungs when you inhale may leave when you exhale, but otherwise they either remain in the tissues of the lungs or enter the bloodstream and migrate to other parts of the body.

As the evidence mounts, it’s becoming more and more clear i) that the home is the site of greatest exposure to microplastics, and ii) that inhalation is probably the main route of exposure there. Early estimates of microplastic exposure at home have been revised after further research suggested exposure levels may be 100 times higher than previously thought.

Microplastics in the home generally come from synthetic fibres: clothing, carpets and furnishings. They accumulate in dust and circulate in the air. Babies and very young children are particularly at risk from microplastics in the home, because they’re close to the ground, where dust accumulates. They just crawl around, hoovering it up all day. Infants have ten times the numbers of microplastics in their feces than adults. The best thing you can is to reduce synthetic fibres throughout the home and also hoover more regularly. Babies are also at particular risk of plastic consumption because they’re given plastic toys to chew, fed with plastic utensils (that they also chew) and also, increasingly, given food that’s stored and then heated in „convenient” plastic pouches that release billions of plastic fragments into the food.

This brings us nicely on to food, and highlights the fact that food storage is probably the biggest issue when it comes to contamination of food with plastic. Food that comes into contact with plastic at any stage of its production, transport, sale or storage will be contaminated. How much depends on a variety of factors. A foundational piece of advice I give to anybody who asks me for advice is to ditch processed food. A nice working definition of processed food is „food that’s prepared outside the home, contains ingredients you wouldn’t typically find in a normal home kitchen”—additives like stabilisers, humectants, preservatives, colour dyes etc.—” and is sold to you pre-packaged, wrapped in plastic.” Processed food is laced with seed and vegetable oils, hidden sugars, toxic additives, endocrine disruptors and microplastics. If you prepare your own fresh, locally sourced food, you will significantly reduce your consumption of plastic, as well as lots of other harmful things.

Chuck out plastic Tupperware containers and buy some glass ones. Use brown-paper or silicone bags for storage rather than plastic bags. Instead of greaseproof paper, get some muslin and wax it with beeswax. Wherever there’s plastic in your kitchen, try and find an alternative: utensils, pans—especially „non-stick” coated pans—everything, or at least as much as you can. Chances are, there is at least one alternative and it’s not actually expensive or an inconvenience, not really.

The same applies to drink as to food. If it’s in plastic, don’t buy it. Don’t store liquids in plastics. If you want to take a drink to the gym, get a glass or metal bottle.

Municipal tap water isn’t actually much of a worry, at least as far as microplastics are concerned, but you should be filtering your drinking water, preferably with a reverse-osmosis filter. Bottled water, on the other hand, absolutely is a worry for microplastics. In fact, bottled water is one of the worst sources of microplastic exposure for anybody who drinks it regularly. Back in 2018, we were told that a litre of bottled water might contain 325 pieces of plastic on average, but new detection techniques have revealed the number is actually more like 250,000.

My own contribution to reducing your exposure to microplastics is my company Kindred Harvest, which sells the best quality tea in bags that are guaranteed to be totally free of plastic. The microplastics in tea don’t just come from the water or the kettle (if it’s plastic): they also come from the teabag itself. A significant proportion of teabags are now either made of plastic—the teabag is actually plastic—or contain plastic, usually in the glue that holds it together. A study of six tea brands in the UK revealed that four included polypropylene and one was made entirely of nylon.

Food-grade plastics deteriorate significantly at temperatures above 40 degrees centigrade. Put a food-grade plastic teabag in near-boiling water, and it rapidly starts to disintegrate, and you’ve got a drink that’s more plastic soup than tea. A 2019 study in the journal Environmental Science and Technology found that a cup of tea produced by one plastic teabag contained 11.6 billion—billion—microplastic pieces and 3.1 billion nanoplastic pieces. Nanoplastics are probably even worse than microplastics, because they’re smaller, which means they can get into places microplastics can’t inside the body.

Kindred Harvest teabags contain no plastic whatsoever. They’re also organic—no nasty pesticides—and independently tested for heavy metals, since many tea blends are heavily contaminated with lead and other toxic metals.

Kindred Harvest can be found on the ZeroHedge Store.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 09/18/2025 – 21:45

2 miesięcy temu

2 miesięcy temu