Central Asia’s Debt Burden To China Examined

By Eurasianet courtesy of OilPrice.com

China has shifted from the world’s largest creditor nation to the globe’s biggest debt collector. Central Asian states owe billions to Chinese entities, but their geographic importance to Beijing is helping protect them from strong-arm repayment tactics.

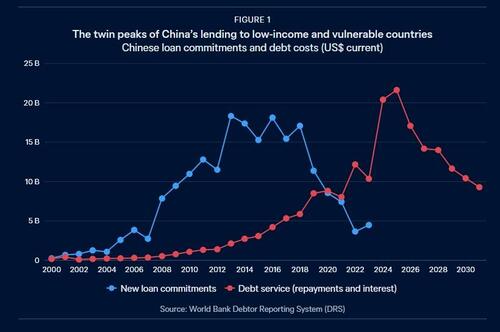

A report issued by the Australia-based Lowy Institute, Peak repayment: China’s global lending, charts China’s transition from “lead bilateral banker to chief debt collector of the developing world.” It shows that China’s lavish loaning under the auspices of its Belt & Road Initiative (BRI) from 2013-2018 is now set to inflict lots of fiscal pain on recipients. Debtor nations, many of them described in the report as “the world’s poorest and most vulnerable countries,” owe $22 billion to China in 2025.

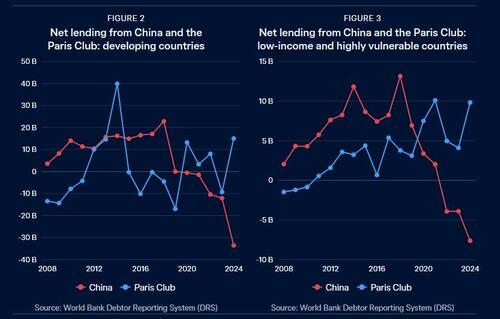

“Beijing has transitioned from capital provider to net financial drain on developing country budgets as debt servicing costs on [BRI] projects from the 2010s now far outstrip new loan disbursements,” the report states. “In 2012, China was a net drain on the finances of 18 developing countries; by 2023, the count had risen to 60. In full, China’s net flows to developing countries dropped to negative $34 billion in 2024.”

At the start of 2024, Central Asian states collectively owed Chinese state entities roughly $20 billion, with Kazakhstan’s having the largest share at $9.2 billion. Kyrgyzstan’s and Uzbekistan’s debts totaled almost $4 billion each, while Tajikistan owed China about $3 billion.

The debt amounts for Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan appear manageable within the context of those nations’ overall GDP numbers, according to economic experts. Meanwhile, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan can be considered prime candidates for falling into a Chinese debt trap. Turkmenistan’s debtor status, given the country’s opaque governing system, is murky, but Ashgabat at the same time is the only Central Asian state running a trade surplus with Beijing, due to its abundant natural gas exports.

A combination of factors is behind China’s transition from lender to debt collector, including the slowdown of China’s domestic economy. But the current surge in debt collection is also a natural outgrowth of the terms of many BRI loans, which included grace periods of up to five years followed by relatively compressed timelines for loan repayment. “Because China’s Belt and Road Initiative lending spree peaked in the mid-2010s, those grace periods began expiring in the early 2020s,” the report notes. “The early 2020s was always likely to be a crunch period for developing country repayments to China.”

Lowy Institute analysts seem to believe China is unlikely to turn the screws on Central Asian states. The report notes that Beijing is continuing to extend loans to “strategic and resource critical partners” including Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.

The change in Chinese lending behavior could well hamper the ability of developing nations, including Central Asian states, to hit growth targets, reduce poverty rates and address global-warming related issues.

“The burden from Chinese debts coming due is also part of a broader set of severe headwinds, particularly for the poorest and most vulnerable economies,” the report states. “An increasingly isolationist United States and a distracted Europe are withdrawing or sharply cutting their global aid support. Reliant on an open, rules-based global trading system, developing economies must also grapple with the impact of new trade-war shocks and the specter of punitive US tariffs being levelled against them.”

Beijing too faces tough geopolitical choices; Chinese officials will need to strike a delicate balance between pressing debtor nations to meet their obligations while not engendering hard feelings that could undermine the country’s geopolitical interests. “Pushing too hard for repayment could damage bilateral ties and undermine its diplomatic goals,” the report states. “At the same time, China’s lending arms, particularly its quasi-commercial institutions, face mounting pressure to recover outstanding debts.”

It’s not just Beijing’s debt-recovery actions that may pose an image problem for the country. An investigative report by the Uzbek outlet Anhor.uz published on June 4 indicated that Chinese entities are engaging in what appear to be predatory business practices in Uzbekistan. The report documents the influx of Chinese companies into the country’s construction sector resulting in a decrease in the price of cement to a point where local Uzbek cement-makers can’t compete and are being driven out of business.

“Over the past two years, almost half of Uzbekistan’s cement plants have ceased operations — only 24 remain, nine of which belong to Chinese companies,” the Anhor report states.

Tyler Durden

Tue, 06/10/2025 – 21:25

6 miesięcy temu

6 miesięcy temu

![Policja ostrzega przed poważnym zagrożeniem w sieci. Nie dajmy się wciągnąć w zasadzkę, szczególnie w święta [SONDA]](https://storage.googleapis.com/poludniowaoficyna-pbem/jarocinska/articles/image/5b892a13-84e2-405a-b067-e2f819bdc8e2)