A Compound Discovered On Easter Island Extends Life, Combats Alzheimer’s

Authored by Flora Zhao via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

Scientists are still uncovering the secrets of a compound discovered 50 years ago on Easter Island. Produced by bacteria there, rapamycin appears to be a powerful life-extender and may be a transformative treatment for age-related diseases.

(Illustration by The Epoch Times)

(Illustration by The Epoch Times)In 2009, the National Institute on Aging Interventions Testing Program (ITP) published a groundbreaking study indicating that rapamycin extended the lifespan of mice by 9 percent to 14 percent. Experiments conducted by various research institutions worldwide have further corroborated these findings or have found the compound to have significantly greater life-extending effects.

The drug also exhibits rejuvenating effects. For example, it can stimulate hair regrowth and prevent hair loss in a short period. It reduces proteins related to aging in the skin and increases collagen. The drug has even shown positive effects in treating age-related diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, as well as diabetes and heart and muscle conditions.

While the drug label for rapamycin currently does not claim to “extend human life,” some people with a strong desire for longevity have already sought this medication from their doctors and take it regularly in small doses.

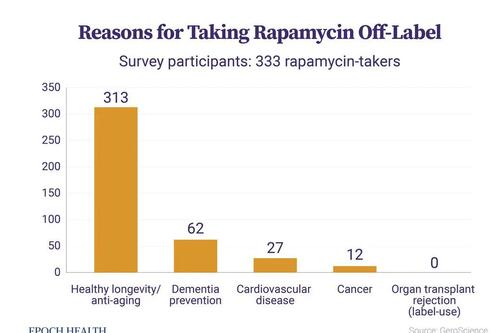

A study published in 2023 in GeroScience employed a questionnaire to survey 333 adults taking rapamycin off-label, most under the supervision of a physician. The vast majority (95 percent) reported taking rapamycin for “healthy longevity/anti-aging” reasons, almost 19 percent for preventing dementia, and a few for “cardiovascular disease” or “cancer.” However, no one reported taking the drug for its original approved use: prevention of organ transplant rejection.

Easter Island’s Hidden Treasure

“Rapamycin was not made in a laboratory. It is not a synthetic molecule. It is actually from nature,” Dr. Robert Lufkin, adjunct clinical professor at the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, told The Epoch Times.

In December 1964, upon hearing about the Chilean government’s plans to build an international airport on Easter Island, a team of 40 people led by Canadian scientists arrived on the island and stayed for three months. Their objective was to explore the island’s population and natural environment before it became exposed to the outside world.

During this period, they observed that the local indigenous people—who walked barefoot—never contracted tetanus, leading the researchers to suspect that some substance in the soil provided protection. Subsequently, in the laboratory, scientists found just that. This substance was a metabolite of Streptomyces hygroscopicus that possessed antibacterial properties.

Rapamycin was extracted from soil collected on Easter Island. Easter Island is called Rapa Nui in the native Polynesian language. (Pablo Cozzaglio/AFP via Getty Images)

Rapamycin was extracted from soil collected on Easter Island. Easter Island is called Rapa Nui in the native Polynesian language. (Pablo Cozzaglio/AFP via Getty Images)This substance starves fungi and things around them and prevents the organisms from growing, Arlan Richardson, professor of biochemistry and physiology at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, told The Epoch Times.

In the local indigenous language, Easter Island is called Rapa Nui. Therefore, the substance discovered in the island’s soil was named “rapamycin.”

Early Uses

In addition to rapamycin’s antibacterial properties, scientists observed that it could also inhibit the growth of animal cells. Rapamycin’s specific target is a cellular protein essential to living organisms called TOR, which acts as a “switch” for cell growth.

“It (TOR) is arguably one of the most important biological molecules ever known,” said Dr. Lufkin, as it fundamentally affects metabolism. It is worth mentioning that TOR derives its name directly from rapamycin. TOR stands for “target of rapamycin,” while mTOR, used in many studies, stands for the “mechanistic target of rapamycin.”

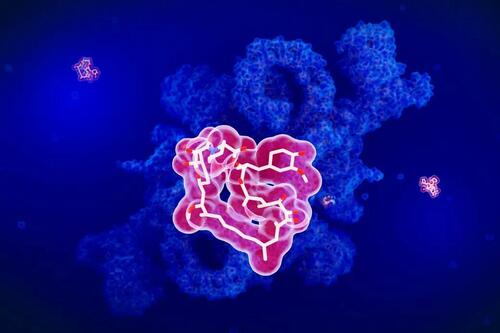

Illustration of the immunosuppressant drug rapamycin (red), also known as sirolimus. It is an inhibitor of mTOR (blue). (Juan Gaertner/Science Photo Library/Getty Images)

Illustration of the immunosuppressant drug rapamycin (red), also known as sirolimus. It is an inhibitor of mTOR (blue). (Juan Gaertner/Science Photo Library/Getty Images)TOR essentially does one thing: It senses the presence of nutrients. When nutrients are available, TOR signals for cell growth. Conversely, when nutrients are scarce, cells stop growing and initiate repair. “And both of those modes are healthy and necessary for life,” explained Dr. Lufkin.

Rapamycin was initially used as an immunosuppressant. Higher doses of rapamycin (3 milligrams per day) were found to reduce the activity of immune cells, thereby suppressing the immune system’s rejection of foreign organs. In 1999, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved rapamycin for kidney transplant patients.

Due to its ability to inhibit cell growth, rapamycin was later used as an anti-cancer drug. In 2007, the rapamycin analog temsirolimus was first approved for treating kidney cancer. Dr. Lufkin noted that rapamycin is effective against multiple types of cancer, with the FDA having approved rapamycin for use as a primary or adjunct therapy for eight types.

There is a connection between the immunosuppressive and anti-cancer effects of rapamycin. “It appears to have a positive effect on cancer control in patients who have transplants—for example, heart transplants,” said Dr. Lufkin. Due to immune suppression, “the most common cause of death after the transplant is not organ rejection, but it is actually a cancer.”

Mayo Clinic researchers conducted a controlled trial, tracking over 500 heart transplant recipients for 10 years. They found that patients using rapamycin for anti-rejection had a 66 percent lower risk of developing malignant tumors than those using another anti-rejection medication (calcineurin inhibitor).

Rapamycin’s Longevity Effects

Rapamycin’s primary action is to inhibit mTOR, which can induce a fasting-like state in cells, triggering autophagy. This mechanism may contribute to its effects on longevity.

In simple terms, autophagy is the process by which cells recycle and remove their own waste and foreign materials, conserving energy for survival.

Mr. Richardson explained that mTOR sends growth signals to cells, which are crucial for children and young animals, aiding in bone growth, brain maturation, and other developmental processes. However, this signaling pathway may adversely affect older adults and mature animals. With age, mTOR can become overactive due to disease or oxidative stress—similar to constantly pressing the gas pedal while driving a car. This renders cells hyperfunctional, contributing to age-related diseases and even cancer.

Read more here…

Tyler Durden

Mon, 04/29/2024 – 05:00

1 rok temu

1 rok temu